Digital Art Gallery

Artem Amare est Vivere

Art can and does take many forms. Art is about the expression of desire by a human being who feels a sensation, an emotion, possesses a will, and works within a medium to realize those attributes. Sometimes the medium is a speech, meant to be spoken aloud and relying on the unique emphasis afforded by the human voice. In other instances, the medium takes the form of something far more tactile and utilitarian such as a necklace or a ceramic bowl. Most often though, for the great apes are nothing if not visually gifted creatures, the medium takes the form of vivid, visual art. This is the realm where every drawing, painting, lithograph, woodcarving, rock art, and sculpture ever created lies. These are inherently media that are intended to be appreciated and approached on that level. Words can never hope to describe them, no matter how hard a writer might labor. To understand these artworks is to see them. To see them is, to analyze and come closer to realizing the essence of the human spirit in ourselves, and in others.

To that end, I have herein compiled numerous visual art pieces that habeas elicited some substantial emotion or introspection within me and that I feel is worth sharing. Most are paintings of various schools, time periods, and intention, but a select few may be more akin to drawings or share familiarity with sculpture. I want to note that due to the limitations of the digital world and the early 21st century where holograms are not yet commonplace, there is a certain... depth lacking in most of these pieces. It is one thing to see an image of one of these artworks but it is wholly another to behold them as physical objects, with your own eyes. This is especially true for sculptures, which in this case can only be viewed fron a single angle. In any event, I hope that this modest, digital art gallery proves enriching for both myself and any who happen to find it. - Qal

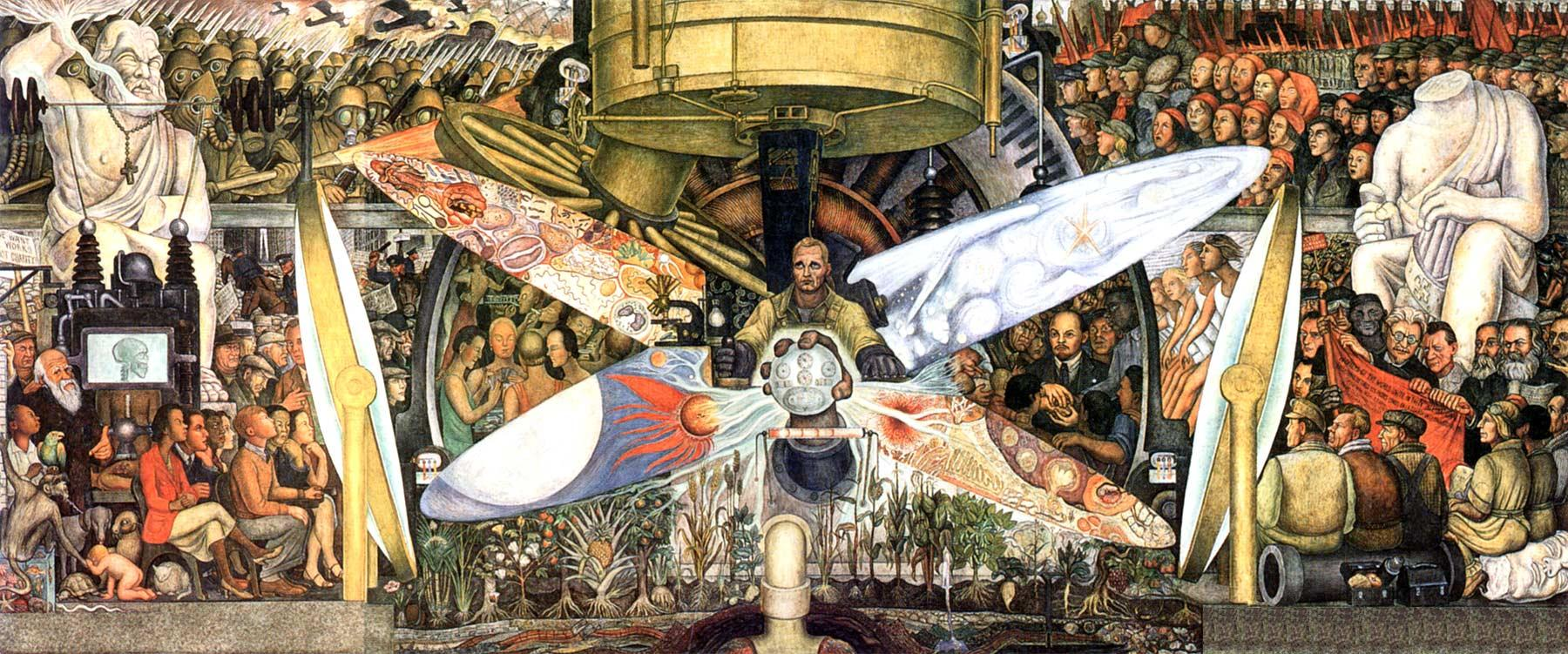

Man at the Crossroads

by Diego Rivera

One of the classes that I took at university was the History of Modern Latin America in order to fulfill the requirements for a History minor. My final project for that course was a 10 minute presentation on the political, social, and cultural context of the Mexican Muralism Movement and so as a result I spent several weeks going over the works of Diego Rivera, David Alfaro Siqueros, and Jose Clemente Orozco. While Siqueros and Orozco have some absolutely spectacular works, both mural and not, for reasons of impracticality/couldn't find a high quality photograph of them, I wasn't able to include them. Thankfully however, I was able to inaugurate this digital art gallery with one of Diego Rivera's most famous murals. Originally, this mural was going to be in a Rockefeller property but was scrapped because of the inclusion of Karl Marx. As for why I find this mural so captivating is the spectular use of imagery to convey politial ideas. The theme of the mural is to examine how man in the 20th century was at a truly spectacular crossorads where the forces of hatred and war were combating the ideals of liberty, justice, and scientific and cultural progress. Contrast is constantly made. On either side of the central figure, there is a scene of Vladimir Lenin aiding the impoverished Russians in their fight for freedom. Opposite Lenin can be seen people playing card games and smoking cigars, signifying upper-class activities of the early 20th century to contrast with the plight of the proletariat. Beyond both of these scenes we one hand beautiful women, dressed in white and illuminated, marching in harmony. In contrast, a scene depicting the chaos of a ciivl protest and police brutality in response is to be found oppposite it. beyond all these, the learned both in science and in political action are to be seen on the flanks, while above them the people emboldened by socialist thought are prepared to combat the faceless, almost in-human industry of war. All of this is united by the central figure, who is shown to be at a console, signifying his control over the situation. He is Man, who can see both the microscopic and the distant suns of the deep cosmos, and he alone has the power to decide what path human history will take. While this mural and the many others like it are not necessarily the most aesthetically pleasing like Renaissance art tends to be, it is perhaps the richest in messaging of any art movement I have yet encountered.

by Eugène Delacroix

La Liberté Guidant le Peuple

"Allons enfant de la Patrie/Le jour de gloire est arrivé!"

Honestly, I could delve deep into the symbolism in this painting. I could go over how and why Liberty is depicted the way she is and I could provide all the historical context of why this painting was created (It wasn't the actual French Revolution from 1789, it was the French Revolution of 1830). Frankly though, it wouldn't be worth my time as that's not why I love this painting. I love it because it so dramatically captures the sense of resistance, of the desire to fight for liberty. It is a genuinely inspiring artwork in that it doesn't just depict a defiant Liberty or a defiant populace, it depicts both, bound together by the desire to bring about freedom for all who are oppressed. In its combination of so many elements, it captures the chaos of the fight for freedom, but also instills the will to seize the moment and do whatever is necessary to secure liberty and prosperity at any cost...

Viva la Revolution!

Lamentations over the Death of the First-Born of Egypt

Charles Sprague Pearce

The Bible is at its heart, an anthology of stories. Whether or not one finds theological meaning in there is frankly, irrelevant, at least when examining the book critically. It is a piece of World Literature that preserves the practices, hopes, desires, anxieties, and cultural motifs of one of the world's most storied regions. I find it valuable irregardless of its place as a sacred text in my culture.

That being said one story within the Bible has always.. fascinated? concerned? scared? me, both on a theological and honestly personal level. That story can be found in the Book of Exodus, where to those unfamiliar, the man Moses who was a Hebrew child saved from a culling of infants when he was a baby, has grown up into an Egyptian prince after being adopted by the royal family. Moses lives in relative opulence until he becomes responsible for a man's death, resulting in his fleeing from Egypt and finding the worship of the Hebrew God out in the desert amongst the Midianites and the Burning Bush. He is called back by God to Egypt to lead the Hebrews out of slavery, but when Pharoah refuses, is directed by God to unleash a series of ten plagues against the Land of Egypt. Amongst other fantastical feats, the River Nile is turned to blood and darkness blankets Egypt for three days and three nights. The final plague however, is the most substantial, and the most haunting. Moses is commanded to inform the Hebrews that God will descend into the land of Egypt and strike down all the firstborn, including the livestock. The Hebrews are spared for they are told to slaughter a lamb and mark the lintel and posts of their doors with its blood to signal to God that they are not be taken.

If you read the text, this is not really dwelled upon and in short order Pharoah will become enraged and attempt to kill the Hebrews. However, various media in the two and a half millennia since this story was written, like this painting, really try to examine the tragedy of what this story represents. Even if it archaeologically, we know this story likely didn't occur as described, its incredibly disturbing to imagine that it could have. According to my culture, this was my God, the being who is supposed to be in all things loving and represent hope. How am I to square the circle that such intense misery, such tremendous grief was wrought, all because of the resistance of a single monarch? The Prince of Egypt (1998) is a great film in how it treats this scene with such dignity, and this painting is truly that sense captured in singular form. In the left of the painting there are deep shadows representing the tragedy that has occurred and seems to envelop all. The figures are seen in a despondent state, man and woman alike, and between them lies a decorated sarcoughagus, suggesting that these are parents who have lost their child and are weeping over their remains. There are even what appears to be the figurines a child might play with, broken, shrouded in shadow, strewn about on the floor while a brazier that once held a flame is clearly now extinguished as wisps of smoke float into the solemn, still air. It is a very powerful image and it truly captures the essence of lamentation. More importantly, it is an artwork that comments on the dismal side of a biblical tale often presented positively.

by Rembrandt Harmenszoon van Rijn

Rembrandt Laughing

There is not actually much to say about this artwork. Rembrandt was a Ducth painter who lived during the golden age of the Dutch in both the cultural and economic sense, and he was very influential to artists downstream. He has many great masterpieces, but I found myself attracted to this simple work. It is a painting of the artist, laughing, and that it is it. It is part of a practice that Dutch painters used to do wherein to study the anatomy of emotion they would paint exaggerated examples of that emotion in portrait form, for no other reason than the honing of their skill. Personally, I find it incredibly admirable as this represents Rembrandt's dedication. Moreover, I find it immensely relateable as he used himself as the subject when it arguably would have been easier to have one of his many students pose instead. I cannot count how many times I have used some photograph of myself or some aspect of my body as either a placeholder, a measurement tool, or model in so many different endeavors. In order to create a photograph once that required blood, rather than simulating it by using jam or paint, I cut myself in order to draw the necessary blood. While this is by no means an equivalent scenario, I can so easily imagine one of these old Dutch painters using their bodies and human form for whatever they felt was necessary to bring about their creative vision, and I adore that.

The Ninth Wave

by Ivan Aivazovsky

This is a painting that comes from 19th century Russia by an artist who specialized in painting marine scenes. Frankly, I love this work for is simultaneous simplicity and grandeur. The scene is simple, a tumultous sea with several survivors of a shipwreck clinging to a floating mast while the warm light of low sun breaks through the dark. Contextually, this is referencing the sense of salvation after the passing of the worst of tremendous waves and the dying of a storm, likely inspired by the artist's actual experience. Personally though, I appreciate the piece a lot more in the sense of calm and tranquility it manages to depict while also showing that there was far more mayhem only minutes, if not seconds before. The crashing of the great wave in the midground and the towering heights of the waves in the backrgound give way to a smaller wave and gentle rolling hump in the foreground where the sailors cling desparately, but securely to the wreckage of their vessel. The light is an obvious allusion to divine intervention or salvation despite great tragedy sure, but I more enjoy how one can perceive the ray of light that illuminates the forward end of the mast as singalling a hopeful future. Similarly, the foreground is most in shadow while further on, golden light shines on the men and penetrates the rolling waves, perhaps in another angle demonstrating that the worst has passed. This is a very inspiring piece both aesthetically and in how it accomplishes a straightforward concept with deep intricacy.

by Lionel Royer

Vercingetorix throws down his arms at the feet of Julius Caesar

Julius Caesar was a very skilled military commander. He was an authoritarian and corrupt man who spelt the end of the Roman Republic, but his strategic prowess is not in question. This is most exemplified in an engagement known as the Siege of Alesia. During the wars in Gaul (modern day France), Caesar was attempting to combat a unified force under the leadership of a Gallic King named Vercingetorix who wanted to repel the Roman presence from Gaul once and for all. As a part of this combat, Caesar found the walled city of Alesia which he began work on besieging. In order to do so, he required that the city be completely cut off from any resupplying of food, water, or manpower and so began the construction of a great wooden wall completely encircling the city. This actually proved successful, capturing the attention of Vercingetorix who rushed to the scene to relieve the besieged. Caesar, in a now famous (and honestly batshit insane move) event then proceeded to construct a second wall opposite the first in order to prevent Alesia from being relieved. In other words, Caesar had consturcted a ring of two walls around the city of Alesia, and had his legions confined within these two walls... and was surrouned by Vercingetorix beyond the second wall, and besieged but still viable Gallic citizens and warriors beyond the inner wall. Well long story short, Caesar actually ended up victorious from this situation and Vercingetorix was forced to surrender and in doing so, marked the end of Gallic independence for several centuries until the Franks (who were technically Germans, not even Gauls) would arrive and invent the concept of France. Importantly though, when nationalism became a big part of 19th century European culture in places like that newly invented place called France I was talking about, many looked to their ancient myths and historical figures for inspiration to define their national identity. The French found Vercingetorix, a warrior king who had stood against Caesar and nearly prevailed. That is what this painting is depicting and I find it absolutely wonderful as a study of symbolism, 19th century nationalism, and the production of our cultural legends. Observe how Vercingetorix is inexplicably bathed in light, clad in bronze armor, still defiant on horseback to sit above Caesar, even in surrender. The imprisoned Gallic warriors to his left and right look up at him in awe and wonder, like the then modern French were doing. The Romans appear pale, disinterested, with their gazes downcast almost as if they were insecure in their victory or at the sight of Vercingetorix. Even then, while Vercingetorix has thrown down his bronze helm, already littering the dusty ground are the discard shields and blades of Roman make, signifying that this was a costly, difficult victory for the Romans. It demonstrates the will and vigor of the Gauls to resist and that even in defeat, they stand taller and more proud than the Romans ever could, for they are in their homeland and will do anything to defend it. In only 25 years time, a mere generation after this artwork was completed, the French would valiantly face the Germans in the First World War to do exactly as their Gallic ancestors did, depicted by this painting. They had done so in the preceding Franco-Prussian War and would be compelled to do so again, and it is artworks such as these that exemplify the Gallic spirit that the 19th and 20th century French sought to capture and evoke.

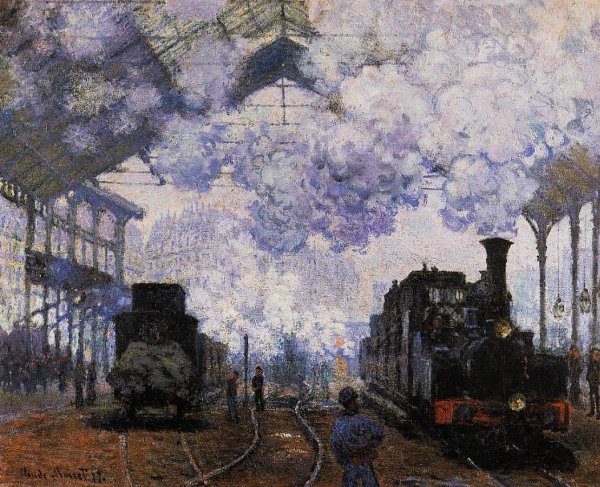

Arrival At Saint Lazare Station

by Claude Monet

This is a rather simple scene of a train arriving at a train station in the late 19th century of France. This is not technically brillaint, nor is it particularly unique aesthetically. But there is something so captivating about Monet's artworks where the use of what I would almost describe as "fuzzy" outlines and a seeming hesitation to ever definitely make a hard border between any subject lends itself so much to personal interpretation and introspection. The scene depicted here was almost certainly a specific event, that occurred at a named and frequented train station, each locomotive was probably a genuine one, and all of this was likely recorded in some log. What I mean to say is that none of this was likely artistic license by Monet, and I have to assume the man in the foreground was based on a genuine individual.. and yet nothing about this image feels descriptive, like a photograph. It feels like a nondescript, example, an impression of what enjoying the fruits of recent industrialization was really like. I seriously admire how the steam coming up from the engine is so puffy and cloudlike to where it is opaque to whatever stands behind it. Have you ever seen steam rising in a large quantity? While not totally, it is transparent to a degree, and yet here is the effect more of clouds. To me that is what helps to solidfy that this is not a one-to-one recreation of a scene but the attempt by an artist to convey an idea, a sense of a scene. A 19th century railway station with a locomotive pulling in. That is what Monet wanted to see as at the time it would have been a novel, powerful scene that demonstrated clearly the technological achievements of mankind up to that point.

by Frida Kahlo

Pensando en la Muerte

Frida Kahlo was an interesting, and in a way, very tragic figure. Incredible heartbreak and anguish colored her life and this shows up in her work. Most of her paintings incorporate her image in some form, and to me that gives a deep introspective, personal, exploratory character to her work. This piece in particular I feel encapsulates these aspects of her body of work into one image where she is pictured singularly before a backdrop of interwoven leaves and thorned branches. If you were to see her as she appeared, you would think nothing of her, or her state of being. Yet, as she chooses to demonstrate by opening a small window into her mind's eye, she is contemplating a desolate landscape with the discarded skull and bones of some unknown person, perhaps herself. She is contemplating death and loss and this dramatically shifts the meaning of her gaze. Without this window she is merely staring in an unaffected, neutral fashion at nothing in particular. However, the glimpse into her psyche transforms her unimpressed stare into one of deep unease, anxiety. She appears slightly troubled but shows no great terror in her eyes, for they have become unimportant while what images her mind's eye are viewing become far more necessary of her attention. This piece has few elements but it is by no means simple and anybody who has ever had visions of the end can very easily relate to this artwork on a profund level.

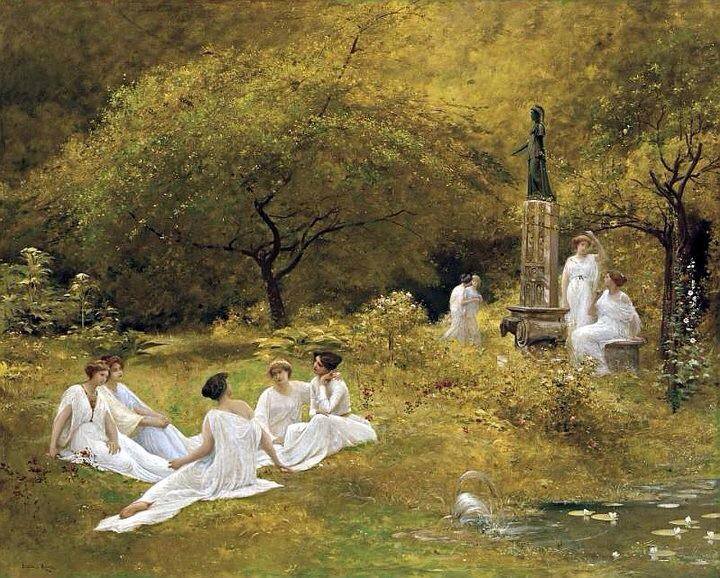

The Muses Garden

by Lionel Royer

To me, the muses have always been representative of inspiration in the way that they are traditionally imagined. Colloquially, you can refer to something as your muse, but in my mind I have always imagined the actual muses being the ones to grant me inspiration. In fact, when I feel the stirring of inspiration I refer to it as, "being hit over the head with a blunt object by the muses" as it tends to describe the massive epiphany that is often accompanied with such a thing. That is why I find myself enjoying this Royer painting so much, because it feels like its affording me a view into an otherwordly garden thats everywhere and nowhere, where the muses just wait and relax until they feel the need to grant me ideas. I appreciate the statue of Athena (Minerva), Goddess of Wisdom who would no doubt have been my patron deity should I have been born in the anicent Greco-Roman World. I also admire how the pond in the foreground has what seems to be a spring as its source, which I can only assume is a reference to how the muses represent an endless wellspring of creative ideas whom mankind can always rely on, even in just a poetic, or in this case, artistic sense.

by Unknown

Scenes From Creation

I have no idea who created this image amd I procured the file through strange means. In any case, I can reliably say that the image dates to the last centuries of the Middle Ages, perhaps somewhere between the 13th and the 16th centuries. The image comes from the tradition of creating illuminated manuscripts which I have long admired. The process of illumination was a lengthy and taxing one, but in many cases was performed as many viewed as an avenue for the adoration of God. In the scene presented this is quite literally was is being done. God, specifically God, the Father, is shown creating Eve from the rib of the sleeping Adam within the Garden of Eden. This image is beyond captivating and it is simply wonderful to look at. More than that though, it is interesting to see the theological and historical inclusions in this artwork that give insight into the Roman Catholic world of the Middle Ages. For instance, and most readily apparent, God, the Father is depicted in the regalia commonly by Popes at the time. Red was a color of opulence in medieval times, but it also symbolized the suffering of Christ and so members of the Holy Trinity are often depicted wearing it, if not already in white, symbolizing purity. The Papal tiara is also seen, in a luxiriant style, which taken politically and culturally, identifies the artist's intent to depict a intimate connection between His Excellency, the Pope in Rome, and God, the Father, both exalted, holy, and leaders of their respective domains. Additionally, in the background of the Garden of Eden one can see the tempation of Adam and Eve by the Serpent as well as perhaps Man and Woman being expelled from the Garden, and a sacrifice to God a mountain beyond even that scene. This is a common practice seen in many illuminated manuscript pages that concern biblical scenes, as the foreground will often depict a specific pivotal moment while the stretching into the background sees the events that follow, such as the Crucifixion of Christ. All in all, I love illuminated manuscripts as an art form.

Allegory of Summer

by Lionel Royer

Rather simply, I just find this a really pleasing painting. It is a pretty, youthful, blonde lady crowned in a wreath, occupying an almost saintly pose, and wielding a sickle. The intent is that this lady be the personifcation of Summer. She is bright, her character seems warm, and you can imagine that any embrace she'd offer you would be tender and welcoming. The way she holds the sickle, the tool of the harvest, and commands her posture, are combined to give off an air of officiality and control that she benevolently uses to ensure a pleasant and comforting season. There are a lot of personifications of the seasons, especially of Spring and Summer, but I have to say that I am quite fond of this particular one.

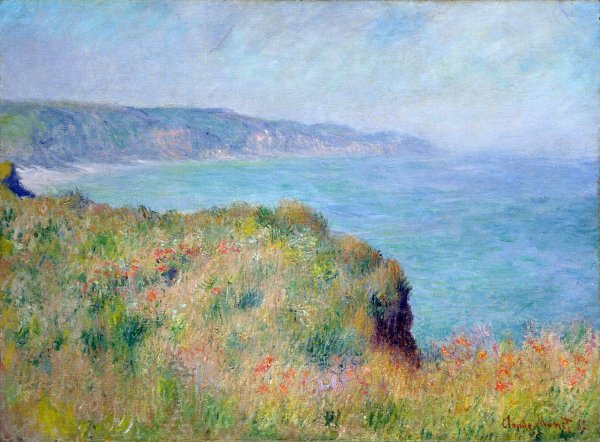

by Claude Monet

Cliff Near Pourville

This piece was the first Monet painting that really, got me. I saw it and genuinely felt a stirring in my chest and was enveloped by all the warm emotions of wonder and fondness that such a piece should engender. When I was a boy, I used to dream of the sea and of the horizon, but lacked the means or circumstances to ever go beyond either. Reading stories and playing video games involving sailing were my form of fulfilling this fantasy, and so often in photographs or in my mind's eye, I conjured up pictures so similar to the one presented here by Monet. In fact, I distinctly remember a scene of a beach, looking off to a calm and calling sea, and wishing with all my might that I could somehow live in a painting. Upon looking at this artwork, the same emotions have stirred in me again.

Moreover, Monet belonged to a school of art known as Impressionism, which aimed to capture the painter's impression of a scene. Rather than Baroque paintings which relied on great and elaborate detail and which dictated a fine line between forms, Impressionism sought to rely on less meticulous crafting of a piece and represented a rejecting in that effect. While skill is no doubt in question, the aim of the painter was to use less strict brushstrokes and a lesser blending of colors to affect less of a description and more of an experience. Here, Monet is painting his impression of this verdant cliff, but nowhere is he telling you that anything is a specific boundary, nor is he saying that one color was the definitive color of the sky nor of the grass. Monet leaves it up to interpretation, presenting his view of what he saw, and offers it up to you to make what you will of it. I for one, make childhood wonder of this impression of that cliff, and I can only wonder what Monet himself did beyond just this image.

The Crucifixion

by Unknown

The Crucifixion of Jesus Christ is one of those events that while shrouded in myth, legend, theology, and historical debate, still grants amazing drama and intrigue. I mean really think about it excepted from all its regular connotations. A man who has demonstrated remarkable powers has predicted his own demise due to the betrayal of a close friend. His remaining friends vehemently deny that they will ever do the same and yet he predicts otherwise. This too comes to pass, and he is sentenced to death in the same breath that a known criminal is absolved. He is mocked and ridiculed as he is made to carry the instrument of his own execution after which he is slain while crying out, "My God! My God! Why hath thou forsaken me!" before giving up his spirit. In a matter of some 24 hours, his friends seemingly lose him to betrayal, and they feel immense guilt for seemingly being apart of that, and are tasked with comforting his widowed mother as she and her companions weep over his corpse. It is a very powerful tale that if it were not the basis for a world religion, it would read as one of the greatest tragedies of antiquity. The Crucifixion presented here is a medieval take on that tragedy and attempts to present it as such within the medium of an illuminated manuscript. The faces of the saints and Christ himself are draw delibrately to exhibit as much sorrow as could possibly be conveyed. Half of the sky is darkened in reference to the biblical passage wherein the sky allegedly darkened after Christ's death which so impressed some of the Romans present that they declared he truly was the Son of God. On a final interesting note, this scene does seem.. mismatched chronologically. During the medieval period biblical scenes were often conceived as occuring with the same conventions as existed in medieval Europe. This is why the Pharoah in medieval depictions often looks like a European King, as long before had Europeans forgotten what Egypt, let alone ancient Egypt looked like. The same is true for the various knights and nobleman seen in this artwork that are obviously intended to be Roman legionaires. This same convention can also be observed in The Knight's Tale from the Canterbury Tales where two ancient Greek warriors are described as being "knights" despite that being anachronistic, and even Theseus being described as a "duke" of Athens.

by Frida Kahlo

The Wounded Deer

This painting honestly just speaks for itself and I don't think any description I could make would do it justice. It is Kahlo depicting herself as a wounded deer with elements in the composition that signify her anxieties and worries about her declining health and social situations. She was a troubled person who had to bear much misfortune in her life, and this painting is a very raw, very emotional expression of that misofortune and all the pain that caused her.

The Barque of Dante

by Eugène Delacroix

The Divine Comedy is largely considered to be one of the greatest works of Italian literature, and it informed much of the Roman Catholic culture for centuries to come. Dante also influenced Chaucer and many French and English language poets in turn. The basic premise of The Divine Comedy is that Dante falls asleep on Good Friday and is led away by his hero, the ancient Roman poet Virgil, through the realms of Hell, Purgatory, and afterwards by an angelic woman through the realm of Heaven. While all three are valuable as works of literature, by far the most captivating is Inferno, the trek through Hell, where Dante and Virgil descened deeper and deeper into the pit of fire and Dante's (the real poet, not the literary character) imagination runs wild. For one, this is where we get the famous line, "Abandon all hope, ye who enter here." However, we are also given some of the creative ironic punishments conceived, like conquerors who reveled in bloodlust in life, are mired in blood in death. This painting is one that depicts Dante and his guide Virgil crossing the River Styx. The damned swim in the River Styx and throw themselves at his barque with Dante fearful in response, while Virgil stands stoically observing, perhaps lamenting that so many souls call this river home. In the actual text, Virgil is among some of the honored of Hell who reside in the place called Limbo, where all the great men who were born before Christ go. This is perhaps why he is depicted with a white aura, signifying purity and an aetherial nature while Dante is depicted as more grounded, as during the text he realizes that since he is still alive during his journey he still makes footsteps while all other characters do not. I greatly admire this artwork and I am also told that it was a technically ambitious piece on the part of Delacroix.

Earthrise

Pale Blue Dot

First Flight

Raising a flag over the Reichstag

Completion of the Transcontinental Railroad